ちえ(Chie)

ちえ(Chie)M, my course mate in a Japanese course, is a big Miyazaki fan. He recommended Chie to me, a Gibly studio-associated production.

The style of drawing is not typically Miyazaki, and the reality setting, in spite of the appearances of 3 superpower cats, is far from the colorful and unconfined imaginary worlds that Miyazaki's works usually feature.

I watched it in French (M's DVD only provided 2 choices: French or Japanese) and managed to understand most of the story, but, inevitably, I must have missed some details that are only disclosed in dialogues . Some episodes and transitions remained unexplained to me, I am afraid.

I like the story which develops along with Chie's simple and everyday life, especially when she struggles to run a barbecue business in order to support herself and her lazy father, and when she acts her optimism when being faced with her parents' divorce. Yet, I don't quite understand another story line which introduces a family feud between 3 cats. Their presence is funny for sure, but I am not yet convinced that they are in any way essential to the narrative.

The Nightmare Before Christmas

The Nightmare Before ChristmasI watched this film for one of my classes before Christmas.

K's brother loved the film as a tragedy. He told me that the story is about the fate that one can never be someone else.

What he said is interesting, I think. Does it mean that someone else is always closer to one's ideal self? Isn't it more difficult to just be oneself?

Or is one's own self always an inconvenient fact that s/he wants to avoid?

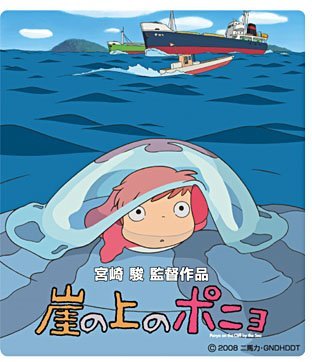

Ponyo

Ponyo is very much a Miyazaki film, presented in vibrant colors and structured by an incredible imagination.

I am not particularly fond of the story itself. What I have enjoyed most in Miyazaki films is the feeling of texture that he can accurately create: the textures of bubbles, jelly fish, ocean waves, and nature. I remember when Ponyo's goldfish siblings try to release their elder sister from a bubble that confines her, they gnawed at the bubble with their toothless mouths. The sound effect and the image work perfectly together that it creates a wonderful sensation of itchiness on the skin as if one's also experiencing thousands of gentle kisses.

Ponyo is such an energetic 4-year-old girl! She does not seem to stop running until she gets where she wants, a very typical Miyazaki character driven by her innocent and powerful determination.